Wise County Outperforms Most Schools in Virginia ...

... The Comprehensive Instructional Program gets the credit. The reality is far more complex.

By Martin Davis

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Email Martin

Fat Boy’s restaurant in St. Paul, Virginia, is well-known — at least in Wise County — for the two BBQ items that sit atop its menu hanging behind the counter. The Heart Attack, and the Stroke.

This 1930’s-era diner, marked by low-rent flooring, plain tables, and chairs that are best described as sturdy but hardly comfortable, proved a more-than-suitable place to sit down and reflect on a day seeing first-hand what makes one of the poorest places in Virginia one of its most academically successful, at least when the measuring stick is Standards of Learning scores.

For the second year in a row, Wise County schools have had the third-best overall SOL pass rate in the state of Virginia. It hasn’t ranked lower than eighth since 2013.

An impressive feat considering it spends less per student than Fredericksburg city, Spotsylvania County, or Stafford County public schools; is riddled with a meth epidemic that has led to a startlingly high incarceration rate of 721 per 100,000 people (Virginia’s rate is notoriously high at 679 per 100,000 people); and nearly 20% of its citizens live in poverty (more than 25% of children grow up in poverty).

In the halls of Richmond’s Department of Education, and among education policy wonks, the reason for the county’s success is captured in a simple acronym — CIP, which stands for “Comprehensive Instructional Program.”

The program alone, however, doesn’t explain why Wise County, where CIP was born, has proven so successful.

There are 65 Virginia school districts participating in the program, says CIP director Matt Hurt, and “we have 10 years of data showing that some school districts adopting the program have great success, while in other districts CIP hardly moves the needle.”

“If that’s true,” I said to Hurt as we savored our BBQ, butter, and sour cream slathered baked potato (Hence, the “Heart Attack”) following a long day of interviewing the administrators and teachers in Wise County responsible for their success, then “the CIP program is misnamed, is it not?”

“In fact,” I continued, “the CIP’s not really a program at all.”

“Agreed,” Hurt admitted.

“We’ve struggled with the name,” he continued, because it’s not the “C” or the “I” or the “P,” or even the bundling of the three, that make the program successful.

“It’s the intangibles.” And in Wise, the most significant intangible is culture.

‘We Have a Job to Do’

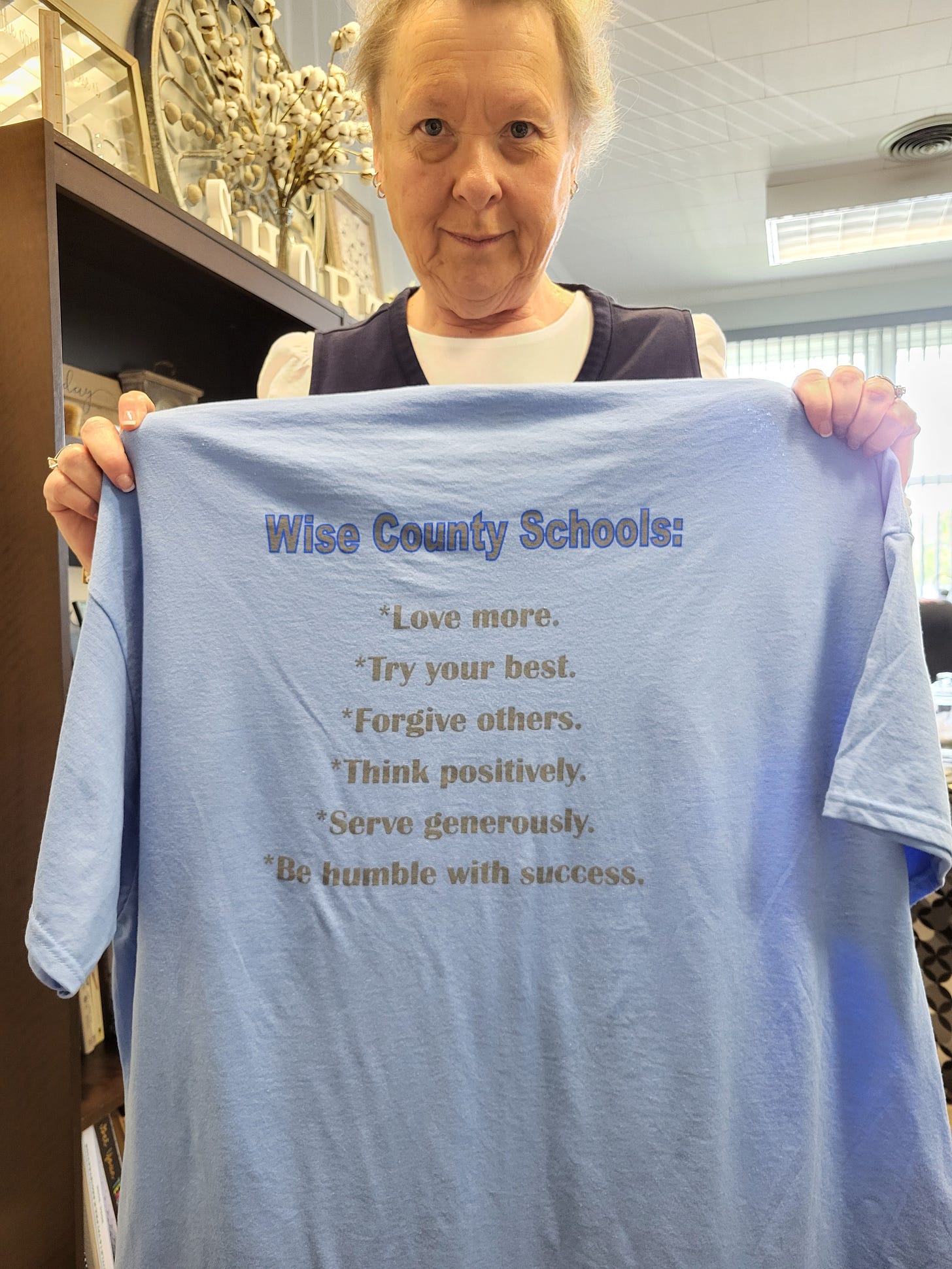

Marcia Shortt is Director of Elementary and Middle Schools in Wise County Public Schools, but with 40 years under her belt there’s little she isn’t directly involved with. Including addressing employees who aren’t making the grade.

Sitting in her office, Shortt pointed to an empty chair where just the day before, she had put a school administrator on an improvement plan.

“That [person’s] school is in the top third in the state,” Shortt said, “but we know they can do better.”

It’s hard to know what’s more jarring — a high-performing administrator being put on an improvement plan, or the way the administrator reacted.

“The person hugged me at the end,” Shortt said, and then told me “I love you.”

The skeptical-minded may say the administrator was trying to play Shortt by appealing to emotion and their personal relationship. That may well be the case. But there’s evidence to suggest that something more-profound is happening here.

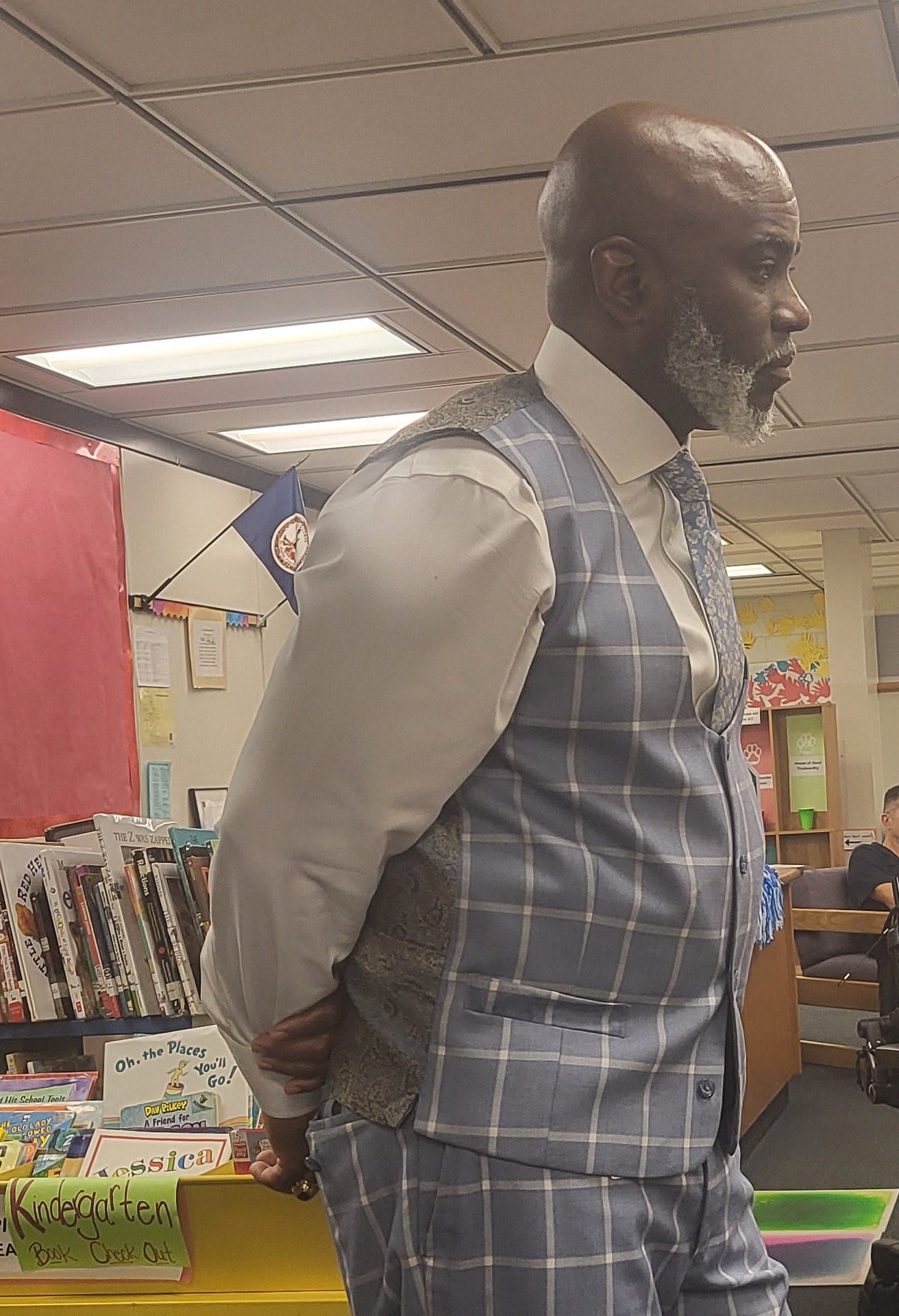

Elijah Helton is the principal of Central High School in Wise, and when asked how he handles difficult discussions with his teachers about their performance, he first had to stop and ponder the last time that had happened.

“I had to talk to one last year,” he said. And while the conversation is never easy, the teacher responded in much the same way the individual responded to Shortt.

“They thought they had let me down,” Helton said.

These atypical responses to trying conversations provide a window into why Wise County has proven so good at getting students to pass the SOL exams.

The CIP program — which is focused on setting high expectations, relentlessly using data to track and measure progress, and leveraging people’s success to create resources that others can follow — gets the credit. However, the program itself isn’t radically different from other programs across the state and nation that do the same. KIPP Academies, for example, depends on the same three elements as CIP.

What’s different in Wise County — and other counties that have successfully adopted CIP — is the culture within the district itself. In Wise County, that means empowering people at every level to do their jobs as they see fit by supporting them in the ways they need supporting.

When things go sideways at a school in Wise, therefore, it’s not the individual who is called to account to explain what went wrong. It’s the leaders above them asking how they’ve failed to support a struggling individual.

This was especially apparent at St. Paul’s Elementary School. Principal Karen Dickenson demands a great deal from her teachers. Passing rates below 95% are unacceptable in her school, and teachers are expected to deliver those results. However, when teachers don’t reach those targets, it’s not the teacher who gets the blame.

“If [the teacher’s class] fails a test, it’s not their fault, it’s our fault,” Dickenson told the Advance. “We’re here to help [them].”

This commitment to fully supporting one another is born of a relentless focus by everyone on two goals: student achievement, and student safety. Anything that doesn’t move the needle in those two areas is set aside for things that do.

These two goals are what central office, administrators, and teachers base their relationships on.

“We’re All In,” Helton told the Advance. It’s a motto he shares with teachers and staff and students. And that means supporting, not criticizing; competing, but not in a spirit that leads not to winners and losers. Rather, it creates an environment where everyone rises together.

“You don’t see a super-structured hierarchy here,” Hurt told the Advance. “People don’t worry about titles. We have a job to do, so we roll up the sleeves and get at it.”

At every turn in Wise County, the singular focus on student success and safety, along with a commitment to supporting everyone at every level, is broadly apparent.

Trust and Support the Teachers

Over the past several years here at home and across the country, teachers in particular have come under fire for everything from poor test scores to being charged with “indoctrinating” children with nefarious ideas and peddling pornography in school libraries.

That type of criticism is largely absent in Wise, despite it being a deep red county where groups like Moms for Liberty have enjoyed success leading revolts against public education and teachers in particular.

The reason this movement hasn’t taken hold is fairly simple. The administrators trust the teachers, and the community in turn trusts the school system.

“When you have the data that shows your success,” Hurt said, it’s hard to make the argument that things are failing.

Wise County schools are thriving not because central office is forcing CIP curriculum down the pipeline and requiring teachers to use it. It’s working because the district sets the goals, and then both empowers and supports its teachers to do their job.

“Our teachers use the CIP,” said Shortt, “but they can use whatever they want to use because we trust them. We tell the principals how much money they have to spend on resource and instructional materials. They order whatever they want in that school. The school district is not approving the resources.”

The lone exception to this are the High Quality Instructional Materials that are now mandated by the Virginia Literacy Act, which the division in Wise has adopted.

Nitpicking teachers and schools about resources runs counter to what principals have found more important in achieving students’ academic success — supporting teachers where they most need it. In the classroom.

“Marcia is communicating what teachers have to produce,” said Hurt, “not what they have to do.”

Shortt followed that thought up by saying “as long as the teachers get the results, I don’t care how they get there. … I’m constantly asking administrators and teachers ‘What do you need,’ and ‘How can I help?’.”

Helton at Central High School takes much the same approach. “I’m hands off,” he said. “I let [teachers] go.”

His primary job with teachers is to get them the resources they need. “If a teacher has a technology issue, I can usually have an answer for them in minutes. If there’s a maintenance request, we get an answer and get the work done.”

This is not to say that Helton doesn’t know what’s going on in his building, however. As our interview wound down, I asked if he could simply walk me around the school.

As we strolled down the hallway, he would pop into a teacher’s room and just say hello, then tell a side story as we left about a challenge or success the teacher had recently experienced. When we walked into a classroom during instruction time, the teacher changed nothing. Her body language, tone, and hand motions were the same when we walked in as when we watched her briefly from the door.

Though subtle, this suggests that the teacher feels both empowered and supported. That she sees Helton as an aid in her work, not a force working against her.

At J.W. Adams combined school, which houses PK-8, Assistant Principal Fran Balthis was clear about how administrators approach their teachers. “We don’t micromanage,” she said. “We have good people in place, and high expectations on them, and they have high expectations for their students.”

“We’re about breaking down barriers and vertical walls,” Balthis said. “Don’t be surprised if you see us in the room teaching. Or cleaning up the hallways when a child gets sick.”

Another way vertical walls are dismantled is not dictating curriculum. Developing resources is not a static issue at J.W. Adams. “We’re always developing resources,” Balthis said, “because children change.”

And when a teacher is struggling in the classroom, administration immediately surrounds them with veteran teachers. “We try to pair them based on personalities,” said Principal Chris Wilson.

Other teachers are on-board. Balthis says that when a teacher sends an email requesting advice from other teachers, “within a few minutes that teacher will have 20 responses,” says Balthis.

St. Paul Elementary School is more hands-on — to a point — with its teachers.

“We’re seeing teachers today come in who have not even done internships,” said Principal Karen Dickenson. So she’s become more intentional about supporting these teachers in their first years. A necessity at a school where an SOL pass rate below 95% is considered unacceptable.

That support takes place in many forms. Mentors and coaches are not just available, but ever-present.

Hannah Perrigan, who taught at St. Paul before being promoted to Family Engagement Coordinator, of which more below, and now assistant principal was one of those people who came in without a depth of experience. Thanks to the support she received, it didn’t take her long to get up to speed.

“Probably three out of every five days,” she said, “there was someone who would be in my room the first year I was teaching.” They were there not to criticize but to support and grow her as a teacher, she said. Particularly as it regards how to teach. Her support system offered guided practice, independent practice, and coaches.

“Our teachers should not have an excuse to not know how to do things,” Dickenson said. “We’re giving them support to let them grow. And then we cut the strings and let them go when they are excelling.”

Administrators Need Support, Too

Teachers are well supported, but so, too, are principals and central office staff who are both supported and held to high standards.

That, in fact, is one of the motivating features of CIP, said Hurt, who stated that a prime feature of the consortium is that it is designed to take some of the weight off central office staff so they can focus on their school administrators.

For Shortt, that means more time with staff at all levels. So tight is the level of trust she has with the people in her district that teachers will frequently go directly to her when they need something. “They don’t have to go to the principals,” she said.

It’s an example of how hierarchy is scuttled in Wise in favor of direct communication with the person any individual feels they most need to speak with.

Shortt also makes a point to be in touch with all her principals by phone at least once a day. Again, for no other reason that seeing if there’s anything that she can do for them.

“Dr. Shortt builds a great relationship with us,” said Dickenson. “Teamwork” is central to everything we do. “We don’t compete.”

This cycle — central office supporting principals, who in turn support teachers, who in turn support students — is a defining trait of the schools in Wise County. And it’s possible because of the level of trust that exists among each level of people in the system.

It Does Take a Village

What sticks out more than the cycle of support and trust that exists among central office personnel, administrators, and teachers is the way in which that commitment to supporting student success has transcended the school walls.

At J.W. Adams, Balthis talked about the way in which the police and schools interact.

When police are called to an incident, if there is a student at that place who witnesses a traumatizing or upsetting event (seeing a parent arrested, or observing police entering their house to serve a warrant, for example), the police will call the principal of the affected child’s school and just say, “Handle [this child] with care today.”

The details of the event are not shared, but the call is a head’s up to be mindful that a student may be in need of additional support. It’s a small thing that delivers big impact.

When the child arrives to school the next day, the school has already alerted the teacher and together they are more-attuned to any unusual behavior or signs of distress.

That level of community support goes beyond first responders.

When someone has a baby in Wise County, the county provides two books and information on child development. Soon thereafter, the school system gets involved, too.

Children receive a book each month, so long as they attend one of the story time events the school district offers across the county. “We want to communicate with these parents from birth on,” said Dickenson. This means that before a child ever enrolls in school, they could already have a two- or three-year relationship with key members of the school system, and an excitement about what school will bring.

Once the child is in school, St. Paul Elementary takes things a step further. It employs a dedicated Family Engagement Coordinator whose job it is to meet with the parents throughout the year. This occurs via school events they put together that bring families into the building, and direct communication with the parents of students who are struggling. These actions tie parents to the school.

It’s also a boon to teachers. The pressure to constantly call parents is shifted off of them onto the Family Engagement Coordinator and administration. While teachers are part of the conversation, the work itself comes off their plate so they can focus on what they need to focus on — namely, instruction.

That attention to communicating and being accessible has many perks, most notably elevating the level of trust people have in the school system.

It also helps parents learn how to teach their own children.

“99.9 percent of people want to help their kids,” said Shortt, “but many don’t know how to help them” with their day-to-day work. “If parents don’t know what to do, and are scared of coming to school, we try and make them feel comfortable and bring them in.”

“We just try and take care of our people,” Shortt concluded, both those in the building and those outside.

Expectations and Actionable Data

If all the discussion of supporting one another, building trust, and strengthening community engagement sounds a bit too much like a Kumbaya sing-along around the campfire, know that this all happens against the backdrop of high expectations and actionable data.

One doesn’t work without the other.

Hurt is primarily responsible for analyzing that data and offering advice on where potential trouble spots are. One of the more interesting approaches to using this SOL data is tracking classes longitudinally to see where issues may be arising.

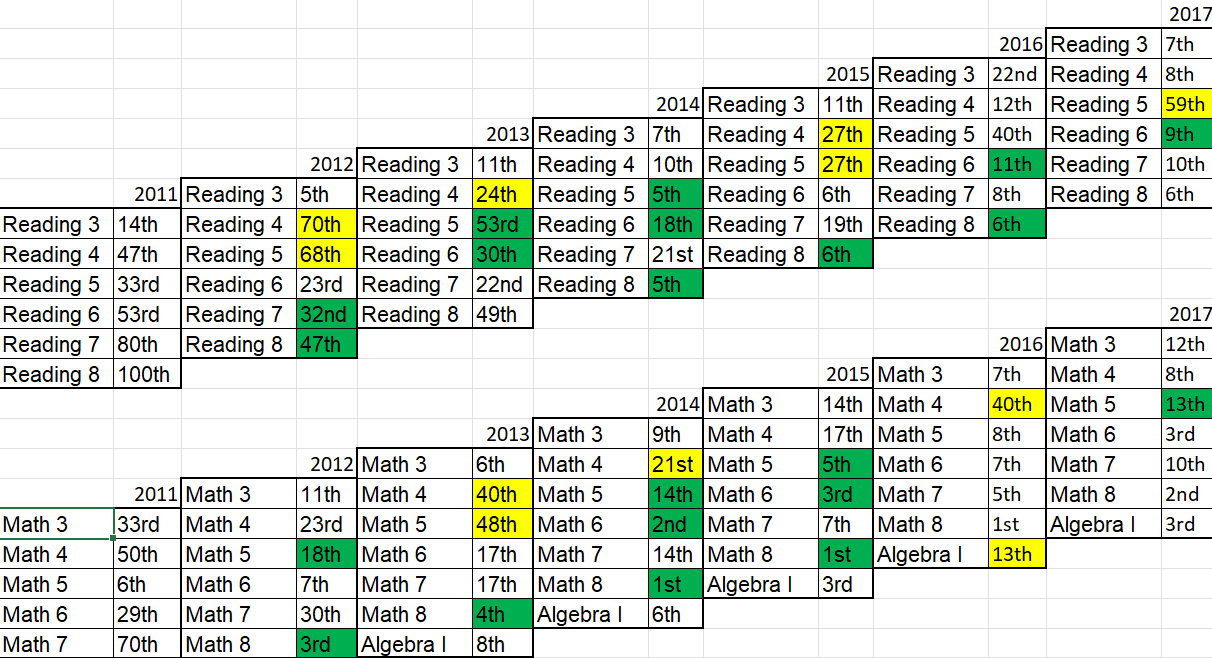

This graph shows how grade levels are performing year-over-year.

Hurt points out that blocks marked in yellow indicate a statistically precipitous drop in achievement. Consider third- and fourth-grade reading scores from 2011 -2013. The 2011 scores showed student performance the first year they took SOL tests in the subject. In 2012, however, when these students have moved to fourth- and fifth-grade, their performance had fallen off sharply.

“We take a problem-solving approach,” Hurt said. That means not placing blame, but working with teachers to figure out the problem and come up collectively with a solution.

“We show teachers the data,” Shortt said, and we also say “We know you’re working hard. However, are you working hard on the wrong things?”

As this chart shows, that approach is working. One doesn’t see a continuous line of yellow along any one cohort of students. Quickly identifying a problem and then working to find a solution means students may fall behind, but don’t for long stay there.

This blending of data and a supportive culture keeps students and schools on track.

Servant Leadership

Shortt is a powerful ambassador for CIP. Her bottom line is simple.

“It’s not training or staff development,” she said, “it’s the people.” And we have “great people,” Shortt said.

That’s reflected in the low turnover rates in schools. At J.W. Adams, St. Paul, and Central, principals report teacher turn-over rates near zero. At J.W. Adams, the district reports a backlog of teachers who want to go there and teach.

Among the key leaders we spoke with, nearly all were lifelong members of the community and of the school system. And each of them independently referenced “servant leadership” throughout the Advance’s stay.

Popularized in the late 1970s, servant leadership is “a … style in which leaders put the needs, aspirations, and interests of their followers above their own,” according to a blog post in the Harvard Law School Program of Negotiation.

The approach to leadership is not without critics. According to the aforementioned blog, “the term servant leadership can seem insensitive when applied to women, people of color, and others who historically have faced marginalization and mistreatment in the workplace and society more broadly. Moreover, few empirical studies have been conducted to test the propositions of servant leadership theory and validate its effectiveness.”

But in Wise County, at least, the core principals of servant leadership — listening, empathy, healing, awareness, persuasion, conceptualization, foresight, stewardship, commitment to the growth of people, and building community — are on full display and validated by the success demonstrated on SOL performance.

Program or Culture?

If there is a criticism of CIP in Wise that critics can rightly point to, it’s the area’s monochrome community. Overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly conservative Protestant Christian, and overwhelmingly in sync with what conservatives would call “traditional family values,” there’s an argument to be made that the culture in Wise schools was easy to build because it’s inbred in the overall culture.

There are numerous counties and cities in Virginia using CIP, however, whose society is not monochrome and they are realizing success.

Before arriving in Spotsylvania, Clint Mitchell was superintendent in Colonial Beach and led the district to a nearly 10-point jump in SOL scores this year. That’s the highest jump in the consortium.

The Advance asked Mitchell about his experience with CIP in Colonial Beach, and whether it can work in more-diverse communities.

CIP in Colonial Beach struggled out of the gate, according to Mitchell, not because Colonial Beach was a more diverse community than Wise, but because of “a lack of leadership and trust” at the principal level. Simply put, teachers were not trusted to “follow the process.”

“My challenge,” he continued, “was allowing the staff at the leadership level to understand that what they were doing was not working for kids, and [they needed] to allow teachers to collaborate among themselves and others in the state of Virginia.”

One principal, a new hire who didn’t carry the baggage longer-serving principals had brought with them, was key to getting buy-in. Once that occurred, others fell in line.

“Once we started to go through the CIP process,” Mitchell said, “it gave us the opportunity to look at our instruction and our pacing and our collaboration among teachers inside and outside the division.”

CIP is “a mindset,” Mitchell told the Advance, that requires “getting people to buy into a structure built on really good trust and collaboration on all three levels. Once you’re able to do that, then you can benchmark with other school divisions. And collaborate with other divisions. I attributed that work to our success.”

For that reason, he believes CIP can work anywhere. “I believe CIP can flourish regardless of the demographic makeup,” he said. “What makes it work is having those three prongs on the same process. Have central office, teachers and leaders having ongoing conversations between themselves.”

And there-in lies the secret to CIP’s success. The program itself, while useful, cannot make change on its own. There has to be a culture of mutual respect, trust, cooperation, and support. Without that, CIP fails.

“Thats’ the part we’re trying to get districts to understand,” said Hurt.

For districts struggling to figure that out, take a trip to Wise, and spend some time with Shortt. Then, head to Fat Boys in St. Paul. It’s the ideal spot to eat and reflect about what is being said, and lived, in Wise County Public Schools every day.

Local Obituaries

To view local obituaries or to send a note to family and loved ones, please visit our website at the link that follows.

Support Award-winning, Locally Focused Journalism

The FXBG Advance cuts through the talking points to deliver both incisive and informative news about the issues, people, and organizations that daily affect your life. And we do it in a multi-partisan format that has no equal in this region. Over the past month, our reporting was:

First to report on a Spotsylvania School teacher arrested for bringing drugs onto campus.

First to report on new facility fees leveled by MWHC on patient bills.

First to detail controversial traffic numbers submitted by Stafford staff on the Buc-ee’s project

Provided extensive coverage of the cellphone bans that are sweeping local school districts.

And so much more, like Clay Jones, Drew Gallagher, Hank Silverberg, and more.

For just $8 a month, you can help support top-flight journalism that puts people over policies.

Your contributions 100% support our journalists.

Help us as we continue to grow!